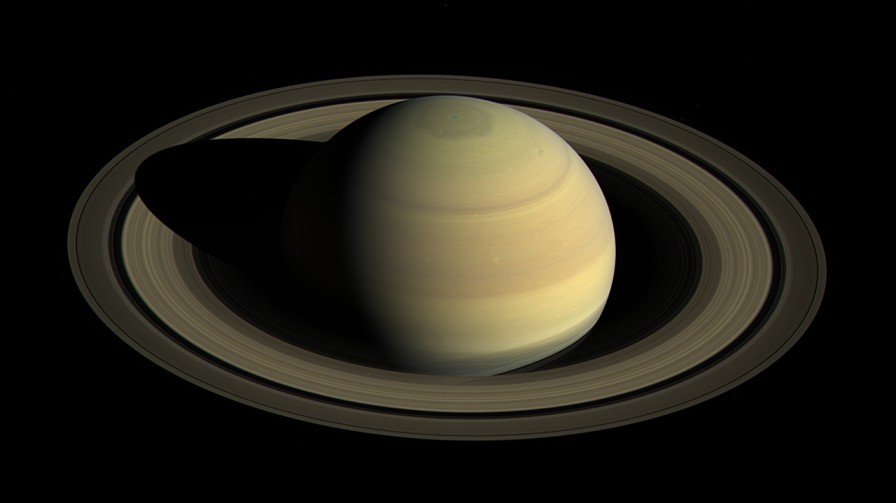

When we hear the term “gas giant planet”, our minds race directly to several planets located within our Solar System, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. These planets share several defining characteristics that allow them to be lumped into the same category.

In particular, the high percentage of helium and hydrogen within their overall composition places them apart from other more terrestrial solar bodies. However, the term gas giant planet is a bit misleading in that it tells us very little about the actual composition of these unique worlds.

Gas giant planets are composed of a high percentage of solid material. Due to the extreme pressure within the core of a gas giant, hydrogen may be converted into a metallic solid or liquid form.

Frequently, there are other materials interspersed within this solid matrix as well. Although all gas giants contain high amounts of hydrogen and helium within their overall composition, they may also have heavier materials such as methane and ammonia. The differences in composition can tell us a great deal about the circumstances under which each planet was formed.

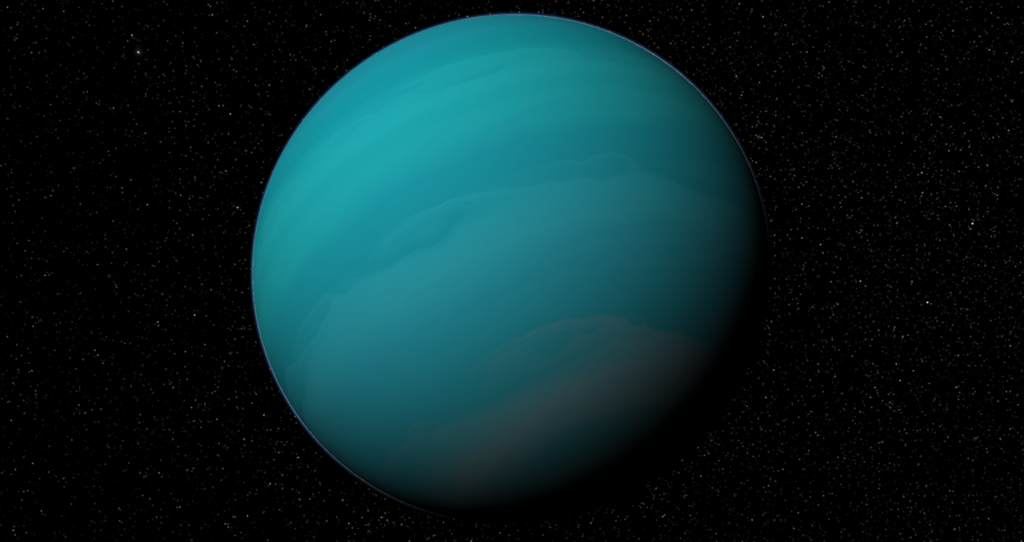

Only Saturn and Jupiter are considered true gas giant planets within our solar system. Neptune and Uranus are now categorized as ‘ice giants’ since their composition comprises heavier elements such as carbon, oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen, with hydrogen and helium making up only about 20% of their actual mass.

During formation, scientists believe that Neptune and Uranus incorporated most of their material as gas trapped within water ice or as ice crystals of various other elements. They are much smaller in size than Jupiter and Saturn, and current research into their overall formation is less understood than their larger cousins.

Classification of Gas Giant Planets

There are a few models of classifying gas giants. One model, Sudarsky’s Gas Giant Classification, categorizes gas giants based on their temperature, albedo, and distance from their star. The more straightforward classification of gas giant planets is the Planetary Habitability Catalog.

Sudarsky’s Gas Giant Classification

David Sudarki and his team performed a theoretical categorization work on gas giants. There are five classifications that ‘Gas Giant’ planets can fall into. Their work was published in 2000 and is still used to categorize newly discovered exoplanets. Gas giants are classified as Ammonia Clouds, Water Clouds, Cloudless, Alkali Metals, and Silicate Clouds. Jupiter and Saturn are classified as type Ammonia Clouds gas giants within our solar system.

Class I: Ammonia Clouds

Ammonia clouds dominate planets in this class, and we are usually found in the outer regions of a star system. They exist at temperatures less than about −120 °C or −190 °F. The temperatures for a Class I planets require either a cool star or a distant orbit. 47 Ursae Majoris c, 47 Ursae Majoris d, Upsilon Andromedae e, and 55 Cancri d are possible Class I planets.

Class II: Water Clouds

Planets in Class II Water Clouds class form clouds of condensed water vapor instead of ammonia clouds. Planets with temperatures below or around -23°C or -10°F usually display these characteristics. Even though the clouds on a Class II planet would be similar to Earth’s, the atmosphere would still consist mainly of hydrogen and hydrogen-rich molecules such as methane. Examples of possible Class II planets are Gliese 876 b and c, Upsilon Andromedae d, and Kepler-90 h

Class III: Cloudless

Class III Cloudless planets have temperatures between about 170 °F or 80 °C and 980 °F or 530 °C. They do not form a global cloud cover because they lack specific chemicals in the atmosphere to form clouds. These planets appear similar to Uranus and Neptune as azure-blue globes because of rayleigh scattering and absorption by methane in their atmospheres. Class III Cloudless planets exist in the inner regions of a star system, roughly as close to their stars as Mercury. Possible Class III Cloudless planets are Upsilon Andromedae c, Kepler-89e, and HD 205739 b.

Class IV: Alkali Metals

Class IV planets’ temperatures are above 900 K (627 °C; 1160 °F), at which point carbon monoxide becomes the dominant carbon-carrying molecule in their atmospheres instead of methane. Class IV and V planets are referred to as “Hot Jupiters.”

Class V: Silicate Clouds

Class V Giant planets are the hottest of gas giants, with temperatures above 1400 K (1100 °C; 2100 °F). Gas giants are likely to glow red from thermal radiation and reflected light. Examples of Class V: Silicate Cloud planets might include 51 Pegasi b and Upsilon Andromedae b.

Planet Habitability Laboratory Classification of Giant Planets

Jovian Giants

Jovian planets share a lot of similarities with Jupiter. Their size is usually six times the radius of Earth and beyond or 50 times the mass of Earth. These planets are generally dominated by hydrogen and helium with trace amounts of water, ammonia, and methane. Jupiter and Saturn are Jovian Giants that inhibit the Cold Zone.

Neptunian Giants

Neptunian giants are 10 – 50 times more massive than Earth and are 2.5 – 6 times larger than Earth in diameter. Neptune and Uranus are Neptunian planets within the Cold Zone. All Giant planets in our Solar System are composed of mostly hydrogen and helium. However, Neptune and Uranus can hold condensed methane in their cold atmospheres, resulting in their greenish and bluish hues.

References:

IAU: Pluto and the Solar System

PHL: Exoplanet Mass Classification (EMC)

PHL — HEC: Periodic Table of Exoplanets

The Astronomy Journey: Albedo and Reflection Spectra of Extrasolar Giant Planets

Research of the Late David Sudarsky

Quincy Bingham is a native Mississippian, world traveler, and digital marketing director. Although his bread and butter is digital marketing, his crowning achievement has been the Solar Republic brand, which embodies his values of kaizen, personal development, and lifestyle design. He has learned through professional and personal experience that change is the only constant in life, trust is the only real currency and consistency is the only vehicle that gets you to where you want to be in life.

He currently resides in Chicago, IL where he assists businesses, agencies, and non-profits grow their organizations with digital marketing and growth hacking principles.